This is a continuation of this article, which focused on learning accelerators. Today, we will discuss the barriers to learning. This philosophy is covered in my upcoming book on the process of teaching the martial arts. Stay tuned and subscribe if you’d like to receive updates!

When studying the martial arts, we must look out for pitfalls that prevent us from learning–or slow down our progress. Please take care not to feel attacked if any of this applies to you, and equally, do not be quick to deny that any of this applies to you as most of it applies to most of us. As you read this article, please ponder if perhaps you have encountered these barriers to learning.

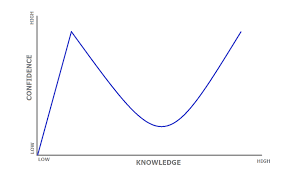

- The Dunning-Kruger Effect (DKE) – Is perhaps one of the biggest barriers to learning, especially if we have had experience in the martial arts and either wish to learn more or wish to access the higher levels of the art. DKE is a cognitive bias that leads to most people overestimating their competence and level of knowledge. According to Psychologists Drs. Justin Kruger and David Dunning, the less we know, the more we tend to overestimate ourselves when self-assessing. In line with the saying that one “knows just enough to hurt themselves”, we often assume that the limited knowledge we possess represents a much higher level of knowledge in the field. Additionally, our untested limited ability is assumed to be much more proficient than it really is. There are really only two solutions or cures to DKE: A painful failure which can crush one’s ego, or to simply learn more. In a graph illustrating how this bias affects us, it shows that we begin the learning process understanding that we know very little. As we learn more, we quickly develop the belief that we know a lot. If we quit learning at this point, we go through life stuck in the delusion. This is where we end up as those eternal yellow belters who pretend to everyone around them that they are nearly experts in the martial arts. However, if we continue learning, we soon discover how much we don’t know and become humbled. As we continue learning, our self-assessment is more accurate and increases as our knowledge increases. We must understand this one thing: DKE affects all of us. This is why it is important to be assessed, to develop a thick skin about the feedback concerning our skill, and to submit ourselves to the guidance of our teachers, mentors, and the opinions and knowledge shared by our peers. Keep learning, and learn as much as you can. This is the only way to combat the bias affecting a vast majority of the martial arts world.

- Fear – This is another barrier that most of us would deny that we have. Perhaps I could have used another term–like anxiety, nervousness, apprehension–but they all result in the same emotion. We have egos that are more fragile than we’d like to admit having. None of us want to be embarrassed, nor do we want to be seen as failures, or the painful realization that we just aren’t as good as we think we are. This is the #1 think that kept most of us from competing. Sure, we say we aren’t in it for trophies, but neither are most of those of us who do compete. Competition is a test outside our walls, uncontrolled by the safety of our teachers, against “unfriendlies”–opponents who are not our classmates and who could care less about hurting our feelings. What we fear about competition isn’t getting hurt–it is the fear of losing. This is the same emotion that keeps wall flowers from getting on the dance floor, what keeps bashful men from asking the pretty girl on a date, what keeps starving salesmen from making “cold” sales calls. We are afraid of rejection, afraid of failure, afraid of the idea that we simply aren’t as good as we imagine that we are. By first acknowledging this emotion, we can then conquer it and move past it. Once you become courageous–which isn’t exactly fearlessness, but the strength to face our fears–we can then elevate to the higher levels of knowledge and experience.

- Cognitive Biases – This is a psychological phenomenon where we process information erroneously in order to adhere to a belief that is more comfortable and pleasing to whatever we would like to believe. There are many forms of bias and many motivations for it. In simple terms, we hold a belief about a subject then either ignore information that may contradict or challenge that belief, we gravitate towards information that confirm that belief, and/or we interpret information that confirms our beliefs while simultaneously refute what we don’t belief. The biggest thing about cognitive biases is that we do not consider truth in any of it. What we think, what we like, must always be the result of what we learn. So if a my belief is that a particular style or technique is superior, I will ignore or misinterpret anything that may be better–and I will only seek out sources that confirm that idea. This is why some Chinese martial artists will refuse to read anything written by Karate practitioners, and why some Filipino martial artists will avoid studying with a Caucasian FMA teacher. This is why some practitioners will only go to seminars and gatherings where familiar practitioners go while avoiding tournaments or gatherings where he may be surrounded by practitioners of other arts. The solution to this is to understand that perhaps your best learning experiences will come from being challenged and tested, even if you are being doubted. It is the most realistic test one can encounter, and it tells you if you truly believe in your school of thought. Learn from sources that confirm your belief as well as those that counter your beliefs. Interact with the like-minded as well as those who think differently. Allow yourself to be questioned, doubted, tested, and challenged. Avoid seeking comfort.

- Lack of Discipline – We tend to think of ourselves as being disciplined and focus, but if you reflect closely you might realize that you aren’t as disciplined and focused as you think. We can all learn to become more disciplined. Doing so will ensure that you will make a lot of progress and do it faster and further than you realize. There are many forms of discipline and all of us can benefit by getting more of it. It may be our consistency, our attention span, even our level of intensity. Some of us may experience lazy days or become easily distracted. We cheat on diets, or skip items on our training regimen. We may not work as hard as we’d like to if we had a bad day at work. Whatever it may be, a good, honest self-assessment never hurts. Once you identify the areas you lack discipline, make sure you hold yourself accountable.

- Peer Pressure – We might think of this as a teenager’s affliction, but all of us may be subject to peer pressure, also called groupthink. It goes something like this. We all belong to a group of some sort: political ideology, religions, martial arts styles, forms practitioners or forms haters, sparring heads or streetfighters, we belong to specific lineages of the arts, or we follow the lead of a particular master or grandmaster. The possibilities are endless. Once we look around in whatever group we are in, even if only online, you might notice certain slogans and phrases everyone uses. There are those who are “in”, meaning they are part of the group to which we belong–or those “others”…. you know, the assholes who have an unrealistic view of the martial arts who have no idea what real martial arts are. Traditional versus modern, purists versus cross trainers, the list goes on. Surely, at some point in your training, you will come to a crossroads where you will think differently than the group. Perhaps you like to do forms. Or you dislike certain types of forms. Maybe you see the value in an art or training method that the group likes to ridicule. Or that teacher everyone calls a fraud–he looks like he knows what he is doing and you’d like to pick his brain or learn his art. Going against the group is very difficult, and very few of us can bring ourselves to disagree with classmates, friends, or lineage brothers and sisters. If you are to have full access to the knowledge available to you, you must be capable of being impervious to the ideas of the group and not giving in to peer pressure. Here is a painful thought: You might even one day disagree with your own teacher and come up with your own ideas. Are you strong enough to do so? Or will your growth and access be affected and limited by the beliefs of the pack?

- No Bullseye – What are your goals in the art? As a beginner, you need not have a specific goal; learning is a lofty enough goal. Once you progress through the ranks–especially once you become a teacher or expert of the art–it is vital that you have a specific goal or set of goals defined. There are many directions to go in the art, and they consist of many levels that are much more difficult to achieve than the Black Belt itself. Whether or not you achieve any of them depends on whether it is a stated goal or just a general direction. If you recall in the last installment, we discussed deliberate practice, which is a goal-specific purpose in training. When you were a student, you simply wanted to learn and achieve proficiency. As an expert, you may want to achieve something much more specialized, such as full-contact fighting, mastery of the art, or creativity in creating a new art/improved art/a second art. Having an internal compass guiding your journey will ensure that you at least get close to achieving those goals. Not having them is almost a guarantee that you will flounder for years and achieve very little.

My book is scheduled to be released in late 2025, and is entitled The Master-Teacher Handbook. It is a treatise on how to teach the martial arts. It is my hope that everyone who reads it will become a much more effective teacher in the long run. If you’d like to learn more and receive updates, please subscribe to this blog and check in with us regularly. We have hundreds of articles on this blog, bookmark this page and see what we have in the archives. If you like anything on this blog, please share and invite others! Thank you for visiting the DC Jow Ga Federation.